Behind the Pitch: Vinny Anand

For this month’s Behind the Pitch, The Film Fund founder Thomas Verdi sits down with filmmaker Vinny Anand to discuss his background in film, how he got his start, and his upcoming short film The Film Fund helped contribute to with a free Adobe Creative Cloud subscription prize, “The Chili Score.”

Thomas Verdi: Can you tell us about yourself and your background in filmmaking?

Vinny Anand: My name is Vinny Anand, and I’m a filmmaker and commercial producer. I started as a comedian in New York City, which led to acting. As an actor, I felt powerless over the types of stories I wanted to work on. So, I began creating my own content with my co-creator, Ronald Austin Jr., who’s been my right-hand man ever since. We’re both first-generation Americans—I’m South Asian, he Haitian American—and we were frustrated by Hollywood’s inauthentic portrayals of our experiences as Americans.

We decided to buck the traditional system and create our own independent TV and film projects. We made a lot of bad stuff initially, but after producing even more, we figured out how to do it effectively on a budget. Friends in the community—other artists and filmmakers—started asking us to help with their projects, so we began producing for others. That turned into a job producing commercials, and eventually directing them. Our commercial production company, FortyLove, sustains our filmmaking careers. Long story short, I started as a comedian, realized I wanted to act, felt powerless, and turned to indie filmmaking because it’s accessible.

Thomas Verdi: It’s a walk in the park, right?

Vinny Anand: Yeah, exactly.

Thomas Verdi: What’s the name of the production company? I’d love to link to it.

Vinny Anand: It’s FortyLove.

Thomas Verdi: Cool. How did you first hear about The Film Fund?

Vinny Anand: I was always searching for grants and support for independent filmmakers. I came across The Film Fund through their logline pitch competition. I had a project I was working on, and I thought the logline was perfect for the contest. So, I submitted it and won.

Thomas Verdi: What’s your winning project about, and what inspired the idea?

Vinny Anand: The project is called The Chili Score, based on a true story. In 2015, there was a ban on Indian green chilies in New York City. I only know this because I’m a hedonist—I love spicy food. Since I was four, I’ve been eating stuff that would crush your insides. I was in New York’s Murray Hill, specifically Curry Hill, on Lexington Avenue between the 20s and 30s, where there’s a strip of Indian restaurants. It’s sad now because Curry Hill has been gentrified, and most of those restaurants are gone, hit hard by COVID.

I was at my local Indian restaurant, and when I got my food, the usual side of onions, lemon, and Indian green chilies—like ketchup with a hot dog—was missing. They said they didn’t have any chilies. I walked out in protest, thinking they were just being cheap. I went to three other restaurants, and it was the same story. I thought, “What the hell is going on?” So, I went to Patel Brothers, an Indian grocery store, walked to the chili aisle, and found just three Indian green chilies in the bin.

To clarify, Indian green chilies aren’t jalapeños. They’re small, like Thai red chilies, but green. Despite the name, chilies don’t come from India—they originated in South America. The chili plant is a fruit, and its spiciness is a defense mechanism to deter animals like humans. Birds, however, don’t feel the heat and are perfect pollinators. They eat the chilies, keep the seeds intact, and spread them across South and Central America. That’s how chilies became widespread there. When Europeans arrived, they saw a market for chilies. The Portuguese, not Columbus, took them from Brazil to Goa on India’s Malabar Coast, and they became known as Indian green chilies.

Spice has driven history—wars were fought over it. Black pepper, for instance, was once incredibly expensive. Most of it came from Goa, and Indian traders colluded to keep prices high by spinning tales about it growing in fiery caves. Europeans believed it, making black pepper a fortune. Indian green chilies are essential to authentic Indian cuisine. Their flavor is unique—earthy, explosive, then it vanishes. No other pepper does that.

Back to 2015, I was freaking out at Patel Brothers, staring at an empty chili bin. Suddenly, I heard thumping and saw an old Sikh man with a turban and broken spectacles walking toward me. It felt like a scene from Shaun of the Dead—everything froze. He looked at the bin, then at me, and said, “No more chilies.” I thought, “This is amazing.” That moment gave me the premise for The Chili Score, but I didn’t know how to frame it yet. Filmmakers need a great premise first. Then, you figure out how to couch it—whether as a TV show or film. A great premise in the wrong medium or tone won’t work.

Thomas Verdi: David Lynch said something similar. He described fishing for ideas and then deciding which medium—painting, film, or book—suits them best. You’re right; a premise might not be a film at all.

Vinny Anand: Most things aren’t films. Films are one of the hardest things to make. I sat on this idea for a while. Time and patience taught me to hold onto a good idea and wait for the right opportunity. In our fast-paced, AI-driven world, something in your consciousness needs time to develop. I was watching Guy Ritchie’s Snatch and thought, “This is it.” The chili scare came from a fruit fly infestation in the Dominican Republic that wiped out the chili crops, which supply the U.S. Indian restaurants and grocers scrambled, trying serranos and jalapeños, but nothing matched the Indian green chili. Restaurants started shutting down because customers stopped coming.

An underground market popped up, with chilies selling for 10 times the price—$25 a pound. I thought, “This is wild.” So, we set The Chili Score in Jackson Heights, Queens, like Snatch. It’s not about Indian people or victimhood—it’s an American story about hustling to make money. What’s more American than that?

Thomas Verdi: How did The Film Fund help bring your project to life?

Vinny Anand: The logline contest was key because it forced me to distill a big idea—spice supply chain issues, an underground world of eccentric gangsters in Queens—into its core elements. It’s easy to get lost in the wrong threads or go down a path that takes time to backtrack from. The contest crystallized the story’s essentials, setting the foundation for the short film and now the feature.

Thomas Verdi: Many winners say the contest helped them nail their logline and figure out what the story is about. You had that same experience. I’ve been running The Film Fund for eight years, and I hear that repeatedly—it strengthens the logline and clarifies the project. It’s awesome you’re working on a feature too.

Vinny Anand: That’s right.

Thomas Verdi: We’ve seen that pipeline before—a short as a proof of concept, then a feature. What challenges did you face during the creation of The Chili Score, and how did you overcome them?

Vinny Anand: Challenges are everywhere, so I’ll break it down by phases. Initially, we planned The Chili Score as a TV series. The story centered on a nephew estranged from his uncle and father. He grew up with them but cut them off after a falling out—his father emotionally blackmailed him, and his uncle never stood up for him. He lives in the city now, but returns to Jackson Heights when his father falls ill, not out of love but duty. He meets his uncle, whom he hasn’t spoken to in 10 years. The uncle convinces him to have dinner, pulling him into his chaotic world. The uncle is a trainwreck who ruins lives accidentally. The nephew gets caught up and has to find a way out.

In the TV series, season one follows the nephew, Chris, helping his uncle out of this mess. He realizes there’s money in supply chain woes and starts to break bad, like Ozark. But TV is hard for unknown filmmakers. We got interest from a big showrunner in India—he’s making the Indian Ray Donovan for Netflix—who loved it and wanted it as his next project. Three weeks later, he bailed for another gig, and we lost momentum. We learned that as new writers and directors, you rarely get to write and direct your own pilot. They want an established showrunner, and there are only a few, all booked for years.

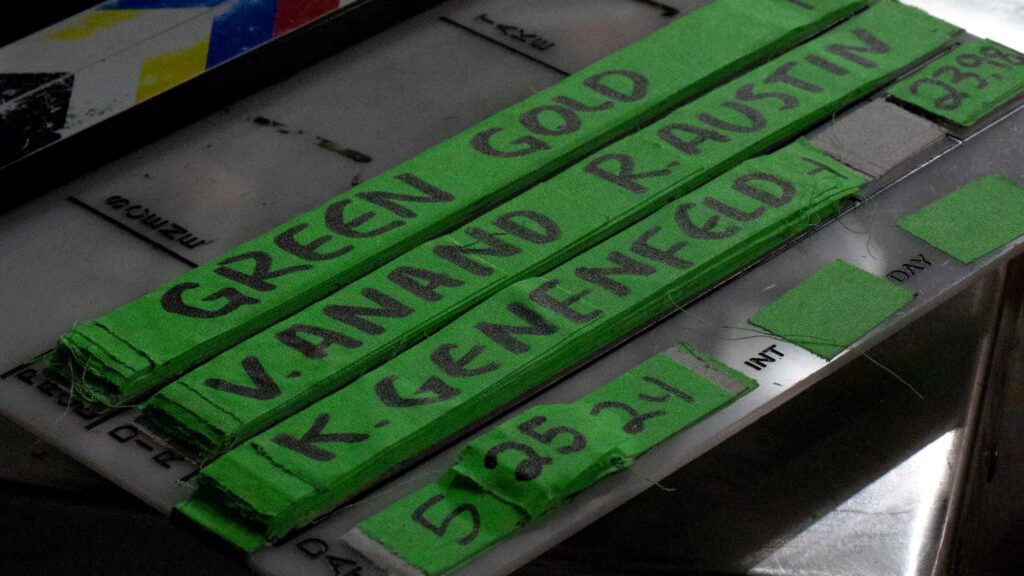

Our producer, Jamal Mallory-McCree from BluRemedi Media, suggested pivoting to a film for more autonomy. He had film contacts and thought it could be a great feature. At that point, we just wanted to make it, whatever the form. To raise funds, we needed a proof of concept. Originally, we planned a teaser, but Jamal convinced us to shoot a short film for festivals and legs. With $4,000, one day, eight pages, four locations, and 10 actors, it was insane. Our commercial production experience—working on tight budgets with hard outs for celebrity-driven shoots—saved us. We pulled in favors: our DP, Ksusha Genenfeld, a top-level talent, shot it; ARRI gave us cameras as the official equipment vendor; a producer got us a free restaurant location for a key kitchen scene. Our producing team made it happen:

- Produced by:

Ambika Sanjana

Jamal Mallory-McCree

Rita Meher - Executive Producers:

Ektha Aggarwal

Manoj Dalmia

Paresh Trivedi

Mandeep Trivedi

Thomas Verdi: That’s incredible—eight pages in one day with 10 actors. Your commercial experience must have been invaluable.

Vinny Anand: Absolutely.

Thomas Verdi: What stage is The Chili Score at now? Are you submitting to festivals or still in post? And what impact has it had?

Vinny Anand: We’re about three weeks from being done. We’re picture-locked, working on the score, color grade, and sound design. Post-production is daunting, especially since Ron and I didn’t go to film school—we jumped in and figured it out. This is our fourth short in three years, and post is the most challenging process. Understanding the workflow and avoiding costly mistakes is critical. You can nail the script, budget, and shoot, but if you hire the wrong person for assembly or run out of money, you’re screwed. Your editor, doing you a favor, won’t touch it without a proper assembly, and your sound mixer needs specific deliverables. It’s heart-wrenching to have the film you want but mess it up due to a mistake, not just money.

Thomas Verdi: It starts in pre-production. On my last short, I communicated the color palette to the colorist but didn’t show the same mood images to the DP. The DP got to post and was like, “This isn’t the intended color.” Post is where you assemble the vision—it doesn’t exist until then.

Vinny Anand: It’s the most important process and the least talked about. We’ve got buzz for The Chili Score because we’ve been at this a while and have the right contacts. The festival route is great, but without a network to get it in front of the right people, it’s tough—there are so many films out there. Our project is unique, like The Interview with Seth Rogen or Birdman, with an erratic score and sound. It’s a narrative that hasn’t been seen much. I stumbled upon a live Birdman screening in Brooklyn with the score performed live—it was insane to see the work behind it. We’ll submit to festivals but also send it to studio contacts we’ve built over years.

Thomas Verdi: What advice do you have for filmmakers entering The Film Fund’s short film contest?

Vinny Anand: Shorts are critical. My co-creator, Ronald, hammered this home. They’re make-or-break for your career because you will mess up—there are too many variables: story, technical aspects, actors, emotions, stress, endurance. The worst thing is to make a feature before doing shorts. Shorts let you develop a rhythm and enjoy the process. Our film is nine minutes, and seeing each layer—sound, grade, VFX, score—come together is affirming, hard, expensive, and wrenching, but so cool.

Thomas Verdi: Shorts are a playground to experiment and find your voice. You don’t want to be finding it on a feature—you need to know what you’re saying and how, visually and otherwise. There’s not a huge commercial market for shorts, but they’re vital for cutting your teeth.

Vinny Anand: Making a film is like building an app. In post, you’re creating something that lives across formats and platforms with a uniform presentation. On set, knowing the terminology—like how to talk to a DP about a shot—makes a difference. It sounds easy, but when everyone’s looking at you, you’re tired, and you’re conveying ideas to actors and crew, it’s tough. If you can’t communicate on a feature, the crew loses faith, and momentum dies.

Thomas Verdi: What’s your best tip for crafting an effective one-sentence pitch?

Vinny Anand: Conflict is key—it’s the core of storytelling. I love comedy, so adding the unexpected, surprises, or a twist is great.

Thomas Verdi: Conflict drives all stories, and subverting expectations is powerful. You can pack both into a logline with conflict-laden words. We have posts on our website about what our judges look for—I’ll link them in the interview.

Vinny Anand: Yeah, exactly.

Thomas Verdi: You mentioned the feature and FortyLove. What are your next steps in your filmmaking career?

Vinny Anand: The Chili Score is a series of films. The short is the appetizer, the feature is the entree, and a second feature is the dessert. The short is a nine-minute music video with plot intertwined. When we wrote the feature that way, it felt gimmicky, so we shifted to a father-son story. A father gets his son involved in the chili mess, digging a hole for him, but it’s more grounded. You connect with the father before the chaos. Don’t get married to how a story appears in different formats. We aim to fund the feature next year and shoot next summer.

I have two other projects I must make before I die. The Royal Inn is a series based on my childhood in Petersburg, Virginia, 15 minutes south of Richmond. It’s a historic town where slaves were brought from Africa to be sold, later booming with factories that then left, leaving it rough. There’s an exit off I-95 with hotels, a hub for travelers, illegal transactions, and workers. In 10th grade, my dad bought a 30-room motel called The Royal Inn. My mom, dad, and I lived there, sleeping on cots. The town was so bad we lied about living with our housekeeper in the next town so I could attend an accredited high school. I’d come home, work the night shift, and clean rooms with my parents. About 85% of U.S. hotels are Indian-owned, so there’s a big story there.

The stuff I saw was crazy—crime, drug dealers, prostitutes, alcoholics, but also nice travelers we’d scam, construction workers, and life. It was tragic and funny. There was a 60-year-old white handyman, Doby, who looked like Jesus with long hair, heartbroken over his wife leaving, addicted to malt liquor. Then there was the “toilet bandit,” a crackhead stealing toilets to sell to other hotels. Condensing units were stolen for copper. It was a rich world, like Severance on Apple TV, which feels like early HBO. Severance’s clean sets, lack of phones, and bleak landscapes are refreshing in our information-saturated world. It makes you laugh and cry, which is where the appetite is now.

The Royal Inn is a series. My parents still run the motel but don’t live there, so we can shoot there. In 2015, Ron and I shot seven-minute episodes called Night Shift, our first project, with Monty Savard and Alyse Ardell Spiegel. It was about Vinny, based on me, and Laquan, a white handyman who looked like Kid Rock, wearing Timberlands, red sweatpants, and a beanie. He’d buy knockoff cologne at Exxon for $4 and douse himself in it, his currency in a place where people had nothing. We’re releasing those on YouTube—they feel fresh now.

The last project is Holy Turban, the pinnacle, another true story. I grew up in Virginia as a Sikh, wearing a turban. My mom’s from Rajasthan, not Sikh, but my dad is. There was no one like us in the state—people thought we were Mexican or couldn’t tell our gender. We got bullied and fought a lot. I cut my hair in eighth grade, my brother in ninth. My immigrant parents worked four or five jobs to give us the best education, sending us to a private school for the American dream. But they were cheap, so we went to a bargain-basement Southern Baptist Christian private school.

Picture a turbaned kid, born in America, learning Sikhism and Hinduism at home, dropped into a Southern Baptist school. I was confused, and that’s where my comedy came from—using it as a shield. My teacher, Mrs. Templeton, saw I didn’t take school seriously but knew I was smart. She said, “I know you’re different, and it’s hard. Apply yourself.” She asked me to enter a Bible trivia contest at Liberty University, part of the Awana after-school program. I thought it was crazy, but I did it for her. I read the Bible for the first time, despite being at the school for years, and liked it. It was like South Asian epics—family drama, wild dreams, wars. As a history buff, I was into it.

I went to Liberty University and won the contest as a turbaned kid. You’d think people would be mad, but everyone stood up and clapped because America loves an underdog. Years later, that scene—a turbaned boy on stage at a Bible trivia contest—inspired me as a filmmaker. The story is magical realism, a comedy about an overweight, schlubby kid who loves basketball cards and stats. He draws Bible figures as basketball players to learn for the contest. At the end, he faces his bully, a pastor’s son, on stage. He doesn’t know the final answer, drops to his knees, and prays—or maybe panics, thinking, “What the hell am I doing?” People think he’s praying. Stained-glass light (a bit fudged for Baptist churches) hits him, a miracle happens, and he knows the answer—a Bible verse about faith. He wins.

Thomas Verdi: Holy Turban sounds amazing. Where can people check out your projects and journey?

Vinny Anand: Our production company is FortyLove at upfortylove.com. Follow me on Instagram at @vinging_it. The Chili Score has an Instagram, @thechiliscore, where we’re sharing the journey. A tip for filmmakers: get someone to do behind-the-scenes (BTS) and stylized BTS. Get as much coverage as possible. You won’t think about it during the shoot, but six months or a year later, when you need to promote, you’ll regret having only a few stills. Promotional materials are as important as the film.

Thomas Verdi: You answered my last question—tips for our community of filmmakers. Want to add another?

Vinny Anand: Holy Turban was the first project I wrote as a filmmaker, and it’s now one of the last on my slate. I spent so much time on that script, cutting my teeth, even getting physical ailments from the stress. It wasn’t right then. Sometimes, projects aren’t ready for you to write—they’re for practice. I moved to shorts and other projects, but Holy Turban stayed in my heart. I wasn’t supposed to make it as my first feature. Have multiple projects, give them time, and keep writing. Consistency is key—show up and write.

Thomas Verdi: This has been awesome. Keep me posted on The Chili Score!